Mr. Thompson is an Academy Award-nominated filmmaker, drummer, D.J., producer, director, culinary entrepreneur and member of the Roots.

I have been collecting things for as long as I can remember. As a very young child, when I listened to music, read interviews or watched movies, they lingered in my memory, and I didn’t want them to leave me. Eventually, I got to thinking about the physical objects that brought me those experiences — vinyl records, print magazines. Collecting those items became a way to prevent the past from slipping away.

A collection starts as a protest against the passage of time and ends as a celebration of it. My collection sprang up like seeds in a flower bed, and I can only guess at the first seeds based on the flowers I see now. Over time it has grown to include bins of magazines, including near-complete sets of Ebony and Rolling Stone.

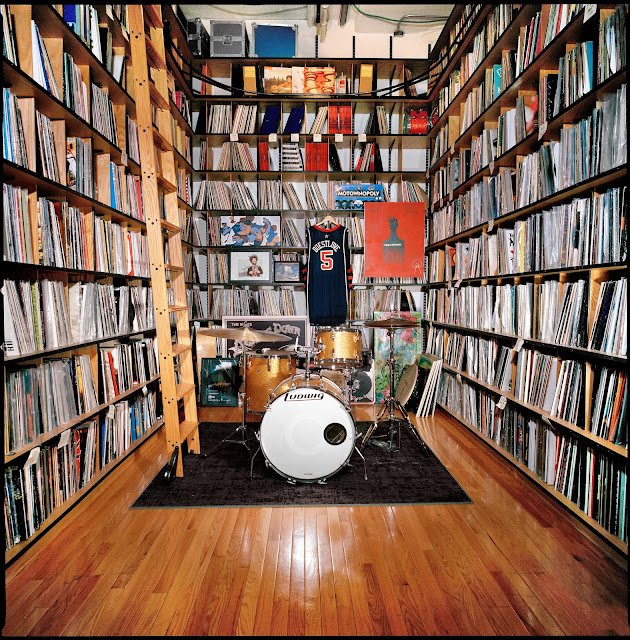

I have shelves and shelves of albums, eight-tracks and cassette tapes. The music they contain — from official studio releases to outtakes, bootlegs to live shows — matters to me. The formats themselves stir memories. But it’s the personal artifacts associated with artists who have shaped my own life and work that are the most meaningful to me.

Questlove’s most precious collectors’ items are associated with the artists who have shaped his own life and work.

Questlove’s most precious collectors’ items are associated with the artists who have shaped his own life and work.Many are connected to Prince: I have a pair of gold-framed mirrored sunglasses that were the backup for those the star used in the iconic 1984 film “Purple Rain,” and the scarf he wore during the Controversy tour. I have a fan letter that Bono, the lead singer of the band U2, wrote to Prince when “The Joshua Tree” album beat out “Sign o’ the Times” for the Grammys’ album of the year in 1988. I also own items from Michael Jackson, Janet Jackson, James Brown, Stevie Wonder and Biggie, among others.

When our lives turned inward as the pandemic began in March 2020, my mind turned toward the past. It felt as if the natural place to go because the future was unclear at best and the present painful. I live-streamed D.J. sets that paid tribute to music icons who had died recently, and sets of self-care slow jams from my collections. I was trying to help people cope by reminding them of the way they used to feel. During this time I also reconnected with many of the objects in my collection. They gave off sparks of comfort.

Keepsakes can evoke emotions like those he felt when he first hung a particular backstage pass around his neck.

Keepsakes can evoke emotions like those he felt when he first hung a particular backstage pass around his neck.As the present felt increasingly endless, my relationship to the past evolved. The D.J. sets became historical in a different sense. The songs I selected evoked not just a feeling, but also the center of a network of ideas, references and questions — a sonic exhibit. I drilled down into my own past when I was asked to go back and work on liner notes for rereleases of Roots records.

Hip-hop has always been historically minded, even curatorial, in the way that it uses samples. Pieces of songs are collected and organized so the past serves the present while still standing up for itself. In this spirit, I sought to understand an object’s significance in its original context as well as the pleasure that it could still produce.

My more recent projects explored how objects on a shelf become subjects in their own right — the way that the collector’s impulse becomes a connecting pulse. In the book “Music Is History,” I looked back across the years I have spent on earth, magnifying an idea from each year, connecting it to a song that represents that idea. And “Summer of Soul,” the documentary I directed, is itself a kind of collector’s item, featuring found footage of the Harlem Cultural Festival, a 1969 concert that featured artists like Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone and Sly & the Family Stone.

The process of directing “Summer of Soul” was considerably more nuanced and intense than organizing a collection, but arranging and commenting upon these long-forgotten scenes required me to ask some of the same questions. What should be displayed prominently? What reflects the main idea most vividly? What’s the best way to make sure that things are not just seen but understood, not just possessed but inhabited?

These projects reminded me that legacy matters, and that mine is largely about illuminating the legacy of the culture that made me. It gives me hope for a future with the confidence to hold the past — to protect it and preserve it, to explain it and elevate it, to keep its light shining brightly even as it drifts out into the sea of time.

Jeffrey Henson Scales & Rebecca Pietri

Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson is an Academy Award-nominated filmmaker, drummer, D.J., producer, director, culinary entrepreneur and member of the Roots. He is the musical director for “The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon” and the author, most recently, of the book “Music Is History.”