It couldn’t have been too surprising that the genre known as chillwave faded out of conversation a couple years after being formulated: After all, it was never a particularly stable term to begin with. Chill — at least in the sense the bands grouped under the label could be said to be chill — is vague and situational, something you know when you see it and not before; wave implies fluidity, inconstancy. Then there was the dubious matter of its invention: Carles, the pseudonymous tastemonger and mocker operating a blog named Hipster Runoff much frequented by “creative” types, had apparently (but only apparently) come up with the term as a joke. To borrow another word that came into wider circulation at the time, the chillwave phenomenon — coined in midsummer 2009, a subject for the Times by early spring 2010 — was a remarkable case of brand inception, the name of the genre preceding the acts that constituted it and molding the reception of their sound well before they could define it on their own. Assuming that there was anything to develop to begin with: As Nitsuh Abebe noted in 2011, this kind of sound — synth-centered and opiate-inflected but still easy to dance to — has been lingering around for decades, mostly in dorm rooms. It seemed a stroke of fortune that the music, atmospheric and sleepy, should find itself in 2009 housed under a Field of Dreams rubric. If you name it, they will sell.

Unreal as it looked, the label had tangible effects, launching a handful of acts into indie-world prominence. And even if it was fabricated out of two-parts hype and one-part fog, it wasn’t completely contrived either. Neon Indian, Washed Out, and Toro Y Moi, the three acts generally acknowledged as standard-bearers, were all one-man acts (respectively, Alan Palomo, Ernest Greene, and Chaz Bundick) who had grown up and were fresh from attending college in the New South, and the latter two were friends and collaborators. If their sound wasn’t as fresh as advertised, the context in which it was received was definitely new. It was the worst economy since the Great Depression (especially for young people trying to enter it), the president was black, and Brooklyn was turning into something it had never been before — a place where people with educational and social advantages flocked in search of cultural currency. The music was cooked up by young men in isolation in the South, but “Brooklyn” and the archipelago of “Brooklyn”-like communities scattered across the nation, invariably became its primary audience. So long as economic horizons were constricted while artistic fantasies were free to range far and wide, the music, bound in a MacBook hard drive yet accessible across the infinity of cyberspace, seemed of a piece with the times.

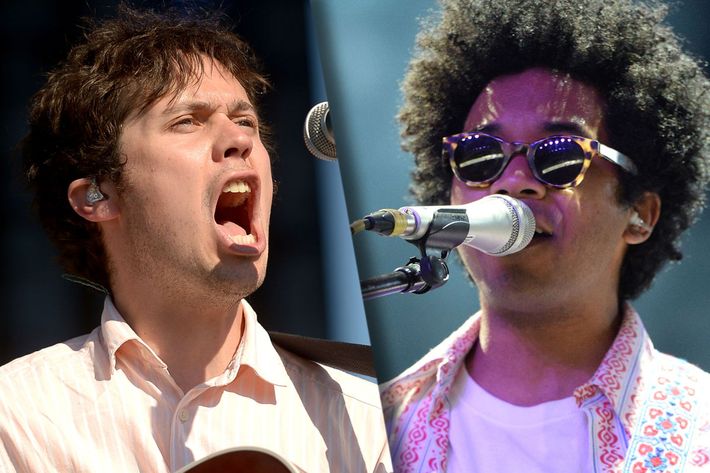

Even though chillwave faded as a hot commodity, its core acts kept putting out music ranging from decent to quite good. Among the chillwave trinity, no one has retired or reached the point where pertinent tastemakers would turn on them outright. They all remain productive: Two Fridays ago Washed Out released a visual album titled Mister Mellow, followed a week after by Toro Y Moi’s fifth album, Boo Boo. If there was ever a time to wonder how they sound and what they stand for in a world markedly different from 2009, it would be now.

Like chillwave, people grow into the names they’ve been given, and Ernest Greene is no exception. Mister Mellow, a 12-track, 29-minute self-portrait in the form of a music video directed by Greene and others, is admirably earnest in its depiction of a blank-eyed dude who doesn’t see much in himself worth saying or showing. Like a botanical specimen calmly drinking in the sun, Greene’s figure is essentially faceless, sometimes even literally, his outline overwritten by a welter of scribbles and absences indicative of a man content to bask in daydreams and bygone images. Even when a breakup with a romantic partner is revisited on “Hard to Say Goodbye” it doesn’t seem to affect the artist, already inclined to indefinite yearning, much.

Though doubtlessly artful, the relentless aura of nostalgia and deployment of toylike visual effects can feel a bit stifling and evasive. The music never dips below a certain level of epicurean comfort, but nor does it ever rise to the point of joy. What the video does clarify is how little chillwave, particularly in Greene’s rendition of it, leans on the natural world: Unlike the nature-centered rock of Animal Collective or Grizzly Bear that preceded it, its basic point of reference is its media representation. The inner life in Mister Mellow, such as it is, has been papered over with old photographs, magazines, and home videos from 25 to 30 years ago. (No sooner had Carles coined “chillwave” than they were suggesting as much: “Feel like chillwave is supposed to sound like something that was playing in the background of ‘an old VHS cassette that u found in ur attic from the late 80s/early 90s.”)

As with prior Washed Out collections, the overall effect can be frustrating precisely because it registers the sadness embedded in this nostalgia as a way of fending off more painful impressions. Or perhaps the listener is meant to feel those for him? Chillwave, as a bankable trend (and Portlandia, as a show with his still-lovely “Feel It All Around” as a theme song), has allowed Greene the uncommon luxury of being able to live as the kind of artist he wants to be. That the artist isn’t much interested in more than modest growth isn’t an issue, because he never claimed to want anything else. Mister Mellow adds a new visual dimension to the Washed Out aesthetic, but the basic laws of that musical universe remain unchanged: nothing abrasive, delicately slurred sound clouds shifting at a tidal pace, neat little things going on the rhythm section, and what can only be described as POMO — the pleasure of missing out. It’s a collection redolent of the soft drugs you’ll require to really enjoy it.

If Ernest Greene makes the music a sentient, sincere, light-drunk houseplant would make, Chaz Bundick, gifted with the Hawaiian shirt of names, seems compelled to generate festive music glowing with a profusion of colors. Boo Boo, like Mister Mellow, is a post-breakup album, but Bundick’s higher concentration of discernible lyrics keeps the haze endemic to Greene’s album at bay long enough to make out enough details to construct a story:

Been so hesitant, I’m such a no-show, why

My baby got fed up with my ego, oh,

Wasn’t even thinking we were going worldwide

Figured it was better than the Southern life

(“No Show”)

My baby got fed up with my ego, oh,

Wasn’t even thinking we were going worldwide

Figured it was better than the Southern life

(“No Show”)

What’s it gonna take for a guy like me to find a girl like you?

What I gotta do to find a girl whose love is more than true?

No one can play the game alone, even if you try to—

Baby, I’m yours now, dreaming a connection

(“Girl Like You”)

What I gotta do to find a girl whose love is more than true?

No one can play the game alone, even if you try to—

Baby, I’m yours now, dreaming a connection

(“Girl Like You”)

Aided by a gorgeous sense of texture and impeccable taste in grooves, Bundick’s hooks drive his collection forward far more than any inventive visualization could. Boo Boo isn’t a straightforward pop collection — Bundick loves to hover in sonic nebulae almost as much as Greene — but his crisp language imparts a direction to his album that his friend Greene’s, content with hazier tendencies, lacks.

Neither man has it in them to hurt anyone directly, but their passivity can sting at a remove. “I don’t think it’s me, I don’t think it’s you, it’s the universe,” Bundick announces, gentle as ever, late in the album, and even if the line isn’t as evasive as Greene’s drowsy indifference to narrative and verbal articulation — Mister Mellow achieves the curious, somewhat poetic feat of being an autobiography without a narrative) — it’s basically a punt. Maybe it’s the universe, but isn’t the universe, at least the fraction of it made up of one and one’s lover, something worth changing, worth looking into further? Then again, stepping too far out of one’s comfort zone would be the antithesis of chill.

In keeping with its recessive nature, the soft-focus quietism at the heart of chillwave has always alluded to the social background of its producers and consumers without ever going so far as to spell it out completely. The ceaseless circulation of the word “summer” in the discourse surrounding chillwave is less vague and universal than it looks: It refers not to summer as a season of deprivation and loss of control, but a summer spent in suburban quiet and prosperity, chilling indoors alone with central A/C, watching daytime TV or listening to music. The “nostalgia” that resurfaces in chillwave and its associated discourse is essentially one where childhood memories of a provided life are superimposed on more current experiences of post-collegiate residency with one’s parents (or at one’s parents’ expense): Whether it’s summer at age 7 or fall at age 23, in both cases school is out and you don’t have a job.

The music is charged with a vague, slightly incestuous sense of never needing to, or being able to, vacate one’s safe space, and vibing with it depends to some degree on feeling shame at not being a self-sufficient grown-up — as well as on feeling its obverse, the regressive pleasure of never having to come out of one’s room and declare oneself. A demographic raised in relative tolerance and comfort, crammed with promises of being anything they wanted to be, graduated college to discover they were useless, surplus waste material a collapsed economy was incapable of absorbing. Chillwave (and the discussion around it) was to some degree a way to cushion the shock of this realization, prolonging a fantasy of plenitude past its actual expiration date. It’s telling that the chillwave discourse died down right around 2011 and 2012, right when the sectors of the economy that employed young “creatives” recovered.

That wasn’t the only reason chillwave subsided, though. Like the hipster, after a while its vagueness became too widespread for the word to be a meaningful descriptor, and like the hipster, the fading of the term itself has coincided with an increasing saturation of what it stood for culturally. Since 2009 dance- and trance-inducing synth-pop shaped on laptops has become ubiquitous; meanwhile chillwave artists (Bundick, in particular) have branched out into guitar songs and live bands. In the wake of chillwave, indie rock is giving way to indie music, a meta-genre defined less by any particular sonic orientation than by a spirit of soft-focus quietism: Even an artist as apparently loud and active as Father John Misty is, examined more closely, espousing beliefs that amount to “It’s not you, it’s not me, it’s the universe.”

So it’s likely that chillwave became a vanishing mediator, its disappearance a sign of its success: It no longer meaningfully describes any one sector in the indie field because it has become identical, in essence, to most of it. It hasn’t changed much in itself, but the world around it has changed to accommodate it — as well as in other ways. “I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space,” declares Hamlet, himself an indecisive kid, fresh from college, who takes pleasure in hiding from himself and the world. It’s all very chillwave until he adds the caveat, “were it not that I have bad dreams.” Nothing could be more timely in 2017, but chillwave’s bad dreams, and the confrontations they imply, are still nowhere to be heard.